|

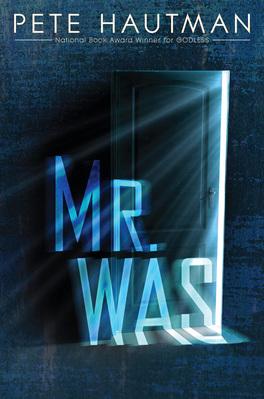

Mr. Was, published in 1996, was my first “young adult” novel. Although not conceived as a novel for teens, when I finished writing the book I discovered that the main character, Jack Lund, was a teenager for most (but not all) of the story. This happened more or less unintentionally. Mr. Was is a time travel story. It covers much of Jack Lund’s life, and it happened that his experiences as a teen made for better storytelling.

When my agent suggested to me that I had written a young adult novel, I was puzzled. “You mean like for people in their twenties?” I asked. Once the realities of marketing books with young protagonists were made clear to me, I happily found a YA publisher for the book, and so began my unplanned but entirely satisfactory career as a writer of books for teens. Here is the first chapter of Mr. Was.This was taken from the orignal manuscript (before copyediting), so there may be an error or two. |

Mr. Was

Chapter One: Meeting My Grandfather

The ringing woke me up.

I turned my head. The alarm clock’s glowing red numbers read 11:59. As the phone rang again, the red numbers changed to 12:00. So that is where we will begin, at midnight, February seventeenth, 1993. It was a long time ago but, as you will see, the memories are still bright and clear.

The phone went silent halfway through the third ring, and I could hear my mother’s low voice. I expected her to hang up right away, because a call in the middle of the night was almost certain to be a wrong number, but she didn’t. I heard my father grumbling about how was a guy s’posed to get a good night’s sleep around this dump. After a few moments I heard my mother hang up.

Everything was quiet for a few seconds, then I heard the shuffling, creaking sounds of someone quietly dressing.

Our rented house, a tiny two-story wooden house in Skokie with just the two bedrooms upstairs, was so small you always knew what everybody else was doing. I heard my parent’s bedroom door open. A bar of light appeared under my door. I heard footsteps on the tiny landing at the top of the stairs. I could tell by the sound that it was my mother, wearing her regular shoes, not her slippers. My door opened. I saw her framed in front of the brightly lit hallway.

I didn’t know what was going on, but I remember getting this feeling in my stomach like something bad had happened. She walked over to my bed and sat down and put a cool hand on my forehead. Mom always woke me up that way, with the hand on the forehead. I loved the way it felt—soft, firm, and comfortably cool.

“Are you awake, Jack?” she asked.

I nodded, staring up at her silhouette, feeling my forehead move against her palm.

She knew I was awake, of course, but she always asked.

“Something has happened.” Her voice had a tightness to it, like the sound it had when she was too mad to yell, but this time there was no anger in it. There was something else.

"It’s your grandfather,” she said. “Your Grandpa Skoro.”

I thought I knew then what she was about to tell me, because I knew that her father, my grandfather Skoro, was getting very old, and his heart was going bad. He lived in a town called Memory, way up in Minnesota, and he was rich. I hadn’t seen him since I was a baby. My mother said that since my grandma had disappeared he’d turned into sort of a hermit and didn’t like visitors, especially kids. I didn’t remember him at all. Every few months Mom would drive up to see him. She said it was to make sure he had enough kipper snacks, rye bread, and corned beef hash. And to give him a chance to yell at her. She would always laugh when she said that.

I had always stayed home with Dad, who also liked to yell at her. While she was gone, Dad and I would eat a lot of pizzas and he would drink a lot of beer. He told me that Skoro didn’t care for our sort of company. Once when Dad was in a bad mood from drinking too much he told me, “Your grandfather is a cheap, mean, hard-hearted old miser. Well he can have his money. I hope he chokes on it.” I always remembered that, because when he said it he threw his beer bottle across the room and broke one of Mom’s favorite collector plates. He gave me ten dollars to tell her I’d been the one who broke it, and I did, but I think she knew I was lying.

...

“Your grandfather is dying,” my mother said, her voice going all high and funny on that last, final word. Her hand was still on my forehead, but it was no longer cool and comfortable. It had become hot and moist and she was squeezing. I twisted my head away and sat up. She locked both her hands together, pushed them down into her lap, and looked away. The light reflected off tears on her cheek. I didn’t like to see her that way.

“Mom? Are you okay?” I asked.

She nodded. “We have to drive up to Rochester,” she said. “They have him in the hospital there.”

“We? You mean we’re all going?”

She shook her head. “Your father’s staying here. He’s not feeling well.”

“You mean he’s drunk.”

She looked away.

“Why do I have to go?” I asked.

“He wants to see you, Jack. He hasn’t seen you since you were a little baby.”

“What if I don’t want to see him?”

“I need the company, Jack,” she said quietly. “Please don’t make a fuss.” Her eyes were filling up with tears again, so I decided not to argue anymore.

...

My mother drove as if she expected to be hit any second. When a big semi would blow by us she would duck her head and swerve toward the shoulder. My father refused to ride with her. He said she was a public menace. But Mom wasn’t the one whose car was in the body shop every few months. Mom wasn’t the one who had tried to drive through the back of the garage. She wasn’t the one who’d got drunk and run over the mailbox.

I watched her cringing and ducking and swerving her way out of Skokie, the one a.m. traffic zooming by, the defroster in the little Honda rattling, straining to clear the frosted windows. I huddled in the passenger seat, hands inside my down parka, my head scrunched down into the collar like a turtle. After a while, the traffic thinned out and the windows cleared and it got warm enough inside the car so I could relax. I had the feeling that Mom didn’t want to talk, but it was pretty boring watching the mileposts flash by.

“I thought grandpa Skoro didn’t like kids,” I said.

She flinched, just like she did when Dad yelled at her.

“Now Jack, that’s not it at all. It’s just ... he’s had a hard time being around people ... ever since your grandmother ... left.”

My grandmother had disappeared about two years after I was born. Some people said she left on her own, others believed something terrible had happened to her. It was a long time ago. My dad said she was probably dead. My mother didn’t like to talk about it..

“So how come he wants to see me now?”

“He’s dying, Jack. Maybe he’s sorry he never got to know you.”

“Well, I’m not.”

That hurt her. She drove in silence for a few minutes, then said, “He is a lonely old man.”

“Dad says he likes to be alone.”

She shook her head. “That’s because your father never knew him. They’re a lot alike, you know. Angry.” She laughed, a high-pitched laugh that I’d never heard from her before.

We didn’t talk much after that, and I think I fell asleep.

...

My whole life, I’ve always hated hospitals. When I tell you what happened, and when you get to know more about me, you’ll understand. This hospital in Rochester was one of the modern kind where they have colored stripes on the floors so you don’t get lost and they try to make things cheery by putting in lots of fake plants in the halls and cheap prints on the walls and the nurses wear bright colors. But it still smelled like a hospital, full of pain and germs and people hooked up to machines.

Grandpa Skoro was hooked up to at least three of them. He had a tube in his nose, another one in his arm, and this thing attached to his chest that led to a complicated looking video display like you see in the movies with the jagged green line going across a screen.

I could hear my mother suck her breath in when she saw him. He looked like he was dead, but the line on the screen was showing these little blips. His bald, crinkled head was white and powdery-looking, a forest of stiff white hairs shot out from his brow, and his open mouth was rimmed with dried spit. The only part of him that had any color was a long, pink scar running along the line of his jaw. Mom moved in closer, leaned over him, whispered, “Daddy?”

That seemed weird, my mother calling this half-dead old man Daddy.

He opened his eyes, pale blue on bloodshot yellow. A grayish tongue crawled across his lips, leaving a glistening layer of spit. He whispered, “Betty.”

She pushed her head in past all those tubes and wires and kissed him on the forehead. I stayed back behind her, wishing I was someplace else. I didn’t want to get any closer. I was afraid. Afraid of the old man and afraid of the nearness of death. I took a step back, thinking that if I could get out into the hall I could lose myself in the corridors and make my excuses later.

But my mother turned around just then and said, “Jack, come say hello to your grandfather Skoro.” She stepped aside so I had a clear view of the old man, and he had a clear view of me.

Grandfather Skoro was smiling, if you could call it that, and reaching out a veiny hand. I started toward him. As I reached his bedside and opened my mouth to say hello, his face changed, as if his flesh were clay in the hands of a mad, invisible sculptor. It began with his mouth falling slack, showing his two remaining peg-like teeth. Then his eyes sort of pushed out of his head and he jerked back away from me like I was a ghost.

“You!” he said, his voice cracking.

I thought, What did I do?

He looked like he was going to die right then and there, but the mad sculptor was not yet done with Skoro. His wide horrified eyes suddenly went small and glittery. His spiky eyebrows snapped together above his long, twisted nose. His mouth went from round to a bat-shaped snarl, and his pale cheeks bloomed fiery red. I don’t remember how he got his hands around my neck, but I remember not being able to breathe, his thumbs sinking deep into my throat and that face, bright red now from forehead to chin, bearing down on me, my mother screaming, the old man’s horrid breath in my face, his wet lips writhing, saying, “Kill you. Kill you. Kill you again.”

...

When I opened my eyes I was flat on my back on the hard linoleum floor, a nurse pressing something cool against my forehead, my mother sobbing hysterically, my grandfather hanging half out of his bed, eyes open and vacant, a bubble of spit frozen on his mouth. The monitor displayed a flat green line, howling its mechanical grief.

The ringing woke me up.

I turned my head. The alarm clock’s glowing red numbers read 11:59. As the phone rang again, the red numbers changed to 12:00. So that is where we will begin, at midnight, February seventeenth, 1993. It was a long time ago but, as you will see, the memories are still bright and clear.

The phone went silent halfway through the third ring, and I could hear my mother’s low voice. I expected her to hang up right away, because a call in the middle of the night was almost certain to be a wrong number, but she didn’t. I heard my father grumbling about how was a guy s’posed to get a good night’s sleep around this dump. After a few moments I heard my mother hang up.

Everything was quiet for a few seconds, then I heard the shuffling, creaking sounds of someone quietly dressing.

Our rented house, a tiny two-story wooden house in Skokie with just the two bedrooms upstairs, was so small you always knew what everybody else was doing. I heard my parent’s bedroom door open. A bar of light appeared under my door. I heard footsteps on the tiny landing at the top of the stairs. I could tell by the sound that it was my mother, wearing her regular shoes, not her slippers. My door opened. I saw her framed in front of the brightly lit hallway.

I didn’t know what was going on, but I remember getting this feeling in my stomach like something bad had happened. She walked over to my bed and sat down and put a cool hand on my forehead. Mom always woke me up that way, with the hand on the forehead. I loved the way it felt—soft, firm, and comfortably cool.

“Are you awake, Jack?” she asked.

I nodded, staring up at her silhouette, feeling my forehead move against her palm.

She knew I was awake, of course, but she always asked.

“Something has happened.” Her voice had a tightness to it, like the sound it had when she was too mad to yell, but this time there was no anger in it. There was something else.

"It’s your grandfather,” she said. “Your Grandpa Skoro.”

I thought I knew then what she was about to tell me, because I knew that her father, my grandfather Skoro, was getting very old, and his heart was going bad. He lived in a town called Memory, way up in Minnesota, and he was rich. I hadn’t seen him since I was a baby. My mother said that since my grandma had disappeared he’d turned into sort of a hermit and didn’t like visitors, especially kids. I didn’t remember him at all. Every few months Mom would drive up to see him. She said it was to make sure he had enough kipper snacks, rye bread, and corned beef hash. And to give him a chance to yell at her. She would always laugh when she said that.

I had always stayed home with Dad, who also liked to yell at her. While she was gone, Dad and I would eat a lot of pizzas and he would drink a lot of beer. He told me that Skoro didn’t care for our sort of company. Once when Dad was in a bad mood from drinking too much he told me, “Your grandfather is a cheap, mean, hard-hearted old miser. Well he can have his money. I hope he chokes on it.” I always remembered that, because when he said it he threw his beer bottle across the room and broke one of Mom’s favorite collector plates. He gave me ten dollars to tell her I’d been the one who broke it, and I did, but I think she knew I was lying.

...

“Your grandfather is dying,” my mother said, her voice going all high and funny on that last, final word. Her hand was still on my forehead, but it was no longer cool and comfortable. It had become hot and moist and she was squeezing. I twisted my head away and sat up. She locked both her hands together, pushed them down into her lap, and looked away. The light reflected off tears on her cheek. I didn’t like to see her that way.

“Mom? Are you okay?” I asked.

She nodded. “We have to drive up to Rochester,” she said. “They have him in the hospital there.”

“We? You mean we’re all going?”

She shook her head. “Your father’s staying here. He’s not feeling well.”

“You mean he’s drunk.”

She looked away.

“Why do I have to go?” I asked.

“He wants to see you, Jack. He hasn’t seen you since you were a little baby.”

“What if I don’t want to see him?”

“I need the company, Jack,” she said quietly. “Please don’t make a fuss.” Her eyes were filling up with tears again, so I decided not to argue anymore.

...

My mother drove as if she expected to be hit any second. When a big semi would blow by us she would duck her head and swerve toward the shoulder. My father refused to ride with her. He said she was a public menace. But Mom wasn’t the one whose car was in the body shop every few months. Mom wasn’t the one who had tried to drive through the back of the garage. She wasn’t the one who’d got drunk and run over the mailbox.

I watched her cringing and ducking and swerving her way out of Skokie, the one a.m. traffic zooming by, the defroster in the little Honda rattling, straining to clear the frosted windows. I huddled in the passenger seat, hands inside my down parka, my head scrunched down into the collar like a turtle. After a while, the traffic thinned out and the windows cleared and it got warm enough inside the car so I could relax. I had the feeling that Mom didn’t want to talk, but it was pretty boring watching the mileposts flash by.

“I thought grandpa Skoro didn’t like kids,” I said.

She flinched, just like she did when Dad yelled at her.

“Now Jack, that’s not it at all. It’s just ... he’s had a hard time being around people ... ever since your grandmother ... left.”

My grandmother had disappeared about two years after I was born. Some people said she left on her own, others believed something terrible had happened to her. It was a long time ago. My dad said she was probably dead. My mother didn’t like to talk about it..

“So how come he wants to see me now?”

“He’s dying, Jack. Maybe he’s sorry he never got to know you.”

“Well, I’m not.”

That hurt her. She drove in silence for a few minutes, then said, “He is a lonely old man.”

“Dad says he likes to be alone.”

She shook her head. “That’s because your father never knew him. They’re a lot alike, you know. Angry.” She laughed, a high-pitched laugh that I’d never heard from her before.

We didn’t talk much after that, and I think I fell asleep.

...

My whole life, I’ve always hated hospitals. When I tell you what happened, and when you get to know more about me, you’ll understand. This hospital in Rochester was one of the modern kind where they have colored stripes on the floors so you don’t get lost and they try to make things cheery by putting in lots of fake plants in the halls and cheap prints on the walls and the nurses wear bright colors. But it still smelled like a hospital, full of pain and germs and people hooked up to machines.

Grandpa Skoro was hooked up to at least three of them. He had a tube in his nose, another one in his arm, and this thing attached to his chest that led to a complicated looking video display like you see in the movies with the jagged green line going across a screen.

I could hear my mother suck her breath in when she saw him. He looked like he was dead, but the line on the screen was showing these little blips. His bald, crinkled head was white and powdery-looking, a forest of stiff white hairs shot out from his brow, and his open mouth was rimmed with dried spit. The only part of him that had any color was a long, pink scar running along the line of his jaw. Mom moved in closer, leaned over him, whispered, “Daddy?”

That seemed weird, my mother calling this half-dead old man Daddy.

He opened his eyes, pale blue on bloodshot yellow. A grayish tongue crawled across his lips, leaving a glistening layer of spit. He whispered, “Betty.”

She pushed her head in past all those tubes and wires and kissed him on the forehead. I stayed back behind her, wishing I was someplace else. I didn’t want to get any closer. I was afraid. Afraid of the old man and afraid of the nearness of death. I took a step back, thinking that if I could get out into the hall I could lose myself in the corridors and make my excuses later.

But my mother turned around just then and said, “Jack, come say hello to your grandfather Skoro.” She stepped aside so I had a clear view of the old man, and he had a clear view of me.

Grandfather Skoro was smiling, if you could call it that, and reaching out a veiny hand. I started toward him. As I reached his bedside and opened my mouth to say hello, his face changed, as if his flesh were clay in the hands of a mad, invisible sculptor. It began with his mouth falling slack, showing his two remaining peg-like teeth. Then his eyes sort of pushed out of his head and he jerked back away from me like I was a ghost.

“You!” he said, his voice cracking.

I thought, What did I do?

He looked like he was going to die right then and there, but the mad sculptor was not yet done with Skoro. His wide horrified eyes suddenly went small and glittery. His spiky eyebrows snapped together above his long, twisted nose. His mouth went from round to a bat-shaped snarl, and his pale cheeks bloomed fiery red. I don’t remember how he got his hands around my neck, but I remember not being able to breathe, his thumbs sinking deep into my throat and that face, bright red now from forehead to chin, bearing down on me, my mother screaming, the old man’s horrid breath in my face, his wet lips writhing, saying, “Kill you. Kill you. Kill you again.”

...

When I opened my eyes I was flat on my back on the hard linoleum floor, a nurse pressing something cool against my forehead, my mother sobbing hysterically, my grandfather hanging half out of his bed, eyes open and vacant, a bubble of spit frozen on his mouth. The monitor displayed a flat green line, howling its mechanical grief.