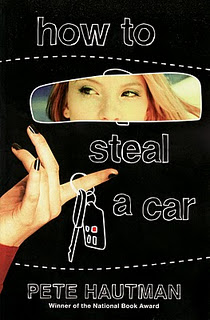

Teacher's Guide: How to Steal a Car

ABOUT THE BOOK

Kelleigh Monahan, a “normal” fifteen-year-old girl living in a Minneapolis suburb, steals a car one night with a friend. She likes it. Over the next few weeks, as Kelleigh experiences a series of disappointments over her friends, her parents, herself, and the novel Moby-Dick, she finds herself stealing another car…and then another.

How to Steal a Car is about one girl’s search for who she is—and who she finds.

See what I mean? You steal one car and all of a sudden all your friends decide that’s what you are. A car thief. —Kelleigh Monahan

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Pete Hautman grew up in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, attended both the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and the University of Minnesota, and worked as a sign painter and graphic artist before turning to writing. In 1991, he completed the novel Drawing Dead which was published by Simon & Schuster two years later. Since then he has authored such critically-acclaimed and award-winning titles as Mrs. Million, Sweetblood and Doohickey. He won the 2004 National Book Award for Godless. When he is not writing, Pete likes to read, run, hike, bike, and cook. He lives in Minnesota and Wisconsin with mystery writer and poet Mary Logue and their two poodles, Rene and Jacques.

THEMES • Alienation • Self-identity • Anger • Friendship • · Family (dysfunctional)

THEMATIC QUESTIONS

Alienation - Many people--not just teenagers--feel alienated. Some people feel alienated because they look different. Some feel alienated because of physical limitations. Others are alienated for psychological reasons: shyness, uncontrolled anger, or behavioral quirks. Why does Kelleigh feel she is different from her friends? Is she really that different?

Self-identity - What is a sense of self? Is it something you are born with, something we are given, or something we invent? Is it possible to change who you are? If you could change your sense of self, who would you become?

Anger - When little kids get angry they yell, cry, and hit. When we get older, we learn to hide our anger in most cases—but anger is a powerful emotion, and we often find ourselves expressing it in self-destructive ways. Examples include saying cruel things to others, driving too fast, drinking or using drugs, and performing dangerous physical stunts. Can anger also drive people in positive ways? What are some of ways that anger can be used to make our lives better?

Friendship - At the beginning of How to Steal a Car, Kelleigh and Jen are best friends. By the end of the book their friendship has cooled. What happened? Was something wrong with their friendship to begin with? How was it affected by Kelleigh stealing cars?

Family - Kelleigh starts out her story by saying how perfect her parents are. But is soon becomes apparent that Mr. and Mrs. Monahan are flawed in many ways. Does that make the Monahans unusual, or do all families have their problems? Is there such a thing as a “perfect” family?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Every time Kelleigh steals a car, she does it for a slightly different reason. What do all of her “reasons” have in common?

2. How does Kelleigh’s story about burning all her dolphin stuff relate to the other things going on in her life?

3. Kelleigh remembers her grandmother Kate as a whiny, complaining old woman, but after Kate’s death, Kelleigh feels a connection with her over an old photo. How does thinking about her grandmother as a teenager affect the way Kelleigh sees the other people in her life?

4. Do you think Kelleigh’s “boyfriend” Will is gay? Why or why not? Is Will’s sexual identity important to the story?

5. Does Kelleigh’s color blindness affect the way she “sees” the world in ways that have nothing to do with vision?

6. Kelleigh’s father is a lawyer who is defending an accused rapist. Is what he does for a living okay? If he knew his client was guilty, would he be wrong to defend him? How does his job affect Kelleigh?

7. What exactly is it that Kelleigh likes about Deke?

8. Kelleigh’s mom tries to be a good mother, but she can’t hide her smoking, drinking, and lying. Kelleigh observes her mom’s behavior without commenting on it much, but how do you think she feels about it?

9. Do you think that Kelleigh will continue to steal cars? Do you think she will get caught?

10. Do you think Kelleigh thinks she will get caught?

RESEARCH AND WRITING ACTIVITIES

1. AUTO THEFT How many cars are stolen in the United States every year? Why do some people steal cars? What is the cost to society?

2. COLOR BLINDNESS Unlike many disabilities, color blindness is invisible. You don’t know if someone is color blind unless they tell you. What are the various types of color blindness? How common is it? How does it affect people?

3. WRITING There were many possible endings to How to Steal a Car. The author chose to end the story on an ambiguous note, with Kelleigh continuing down the dangerous path she has paved for herself. What are some alternate endings? How would you have ended the story?

4. READING Moby-Dick is one of the best known American novels ever written from its famous first line—“Call me Ishmael”—to the amazing battle between Captain Ahab and the great white whale, Moby-Dick. What makes it so important in literature? Why do people keep reading a novel written 150 years ago? How does Kelleigh relate to the novel?

AUTHOR'S STATEMENT

How to Steal a Car is the most polarizing book I have ever written. People love it or hate it.

Some adult readers have trouble with the fact that Kelleigh doesn’t “pay for her crimes” in the end. They complain that there is no “moral” to the book.

They are right about that, in a way. I did not set out to write the book to convince teens that stealing cars is bad. Teens—even teens who steal cars—already know that. There is no debate. Even the world’s most devoted car thief knows that what he (or she) does is wrong.

In an early draft of How to Steal a Car, I wrote a different ending in which Kelleigh steals a car and gets pulled over by the police. As the police officer approaches, she thinks back over her summer, of all the questionable decisions she made, of how different her life has become, and of the terrible price she is about to pay for her sins.

Some people might have preferred that ending. But not me, Jack. I am interested in why people do what they do. I give a lot of credit to my readers—the moral implications of my characters actions are implied rather than explicit.

Here is an excerpt from an interview I did with Euan Kerr at Minnesota Public Radio:

Author Pete Hautman on 'How to Steal a Car'

by Euan Kerr, Minnesota Public Radio

September 15, 2009

Twin Cities novelist Pete Hautman's new book for teens examines life through the eyes of a 15-year-old girl who's an expert at stealing cars.

Hautman's novel, "How To Steal a Car," isn't really a how-to book, but it is aimed at a teen audience.

His research for the book was a bit out of the ordinary.

"I went into one of the local Mercedes dealers and I said, 'I am writing a book about how to steal a car, and I've got a character that steals a Mercedes, and you know, can I take one of your cars for a test drive?'" Hautman said. "The guy looked at me for a long, long time. And then he reached into his desk and pulled out a key, handed it me and said, 'Bring it back.'"

Hautman has a knack for writing for teens. He won the 2004 National Book Award for Young People's Literature for his novel "Godless."

He's said that book's central character, a young man who invents a religion, is based on experiences he had as a teenager. The same is true of "How to Steal a Car."

"I certainly didn't steal cars to the degree that my characters do in the book," he said. "But I had a little joyriding experience that still frightens me when I think about it."

Hautman said he hadn't thought about writing such a story until he was chatting with a group of teenagers about books they wanted to read.

"This one girl said, 'Well, I'm 14 and my life is really boring. And I just want to read a story about a girl like me who goes out and steals a car."

Hautman described it as a revelatory moment.

"There was this flash in my head, [that] this is bringing the teen reading experience down to its most basic element."

Hautman says teens and adults read differently, and they seek different things. He says adults often look to fiction for affirmation in their lives, but teens are after something else. They are looking for experiences.

"They want to know what it's like to go to war, what it's like to have an adult relationship. They want to know about dying, about transcendent joy, and all that kind of stuff," Hautman said. "And because our teenagers here in America lead relatively cloistered lives, they get that information by listening to, or watching, or reading stories."

In "How to Steal a Car," readers experience life through Kelleigh, a 15-year-old Twin Cities girl spending her summer vacation hanging with her pals, visiting well-known stores around the metro, reading "Moby-Dick," and boosting cars.

Kelleigh's life as a thief begins by accident, but she gets hooked on the adrenaline rush. She also begins to see how she is different from her longtime friends -- and relishes that.

"Friendships that are made in childhood don't need to be based on anything except physical proximity," saids Hautman. "But as we grow older and develop more interests, and one person gets interested in field hockey, and the other gets interested in reading books and the other gets interested in smoking crack, interests diverge and it tears these friendships apart."

"And that is part of what Kelleigh is experiencing. She's entering a larger world, but she hasn't found it yet."

When asked how he, as a man, can so convincingly write in the voice of a teenage girl, Hautman says he believes there are actually very few real differences between teenage girls and boys. They have different attitudes and viewpoints on certain things, and he's worked hard to capture those on paper. Otherwise, he says Kelleigh is just a female version of the kid he was at that age.

He says he knows he has it right when he reads reviews. So far, most of those for "How to Steal a Car" have been from adult readers who got advance copies.

Hautman says when half the adult reviewers are upset by the novel, then he's probably hit the right note for his teen audience.

"I don't offer a moral coda at the end. And adults, especially adults reading teen books, they want that," said Hautman. "They want to think that this is somehow a useful tool for their child. But kids should get a lot more credit than they do for being able to figure things out."

from How to Steal a Car:

There was no fuzziness about what Deke and I were doing. It was immoral, illegal, risky, and entertaining. I was not distracted by thoughts of Jen or Will or Jim Vail or Elwin Carl Dandridge or even, in a way, Deke Moffet. Because Deke was not really Deke the Boy, he was more like Deke the Auto Thief. He was not who he was, he was what he did. Like we each had a job to do and until the job was over we were defined by what we did. What we had to do. I think this is why guys like football, and why they join the army because as long as you are playing the game or following orders you do not have to figure out who you really are.